I was.

Couple of interesting things about this.

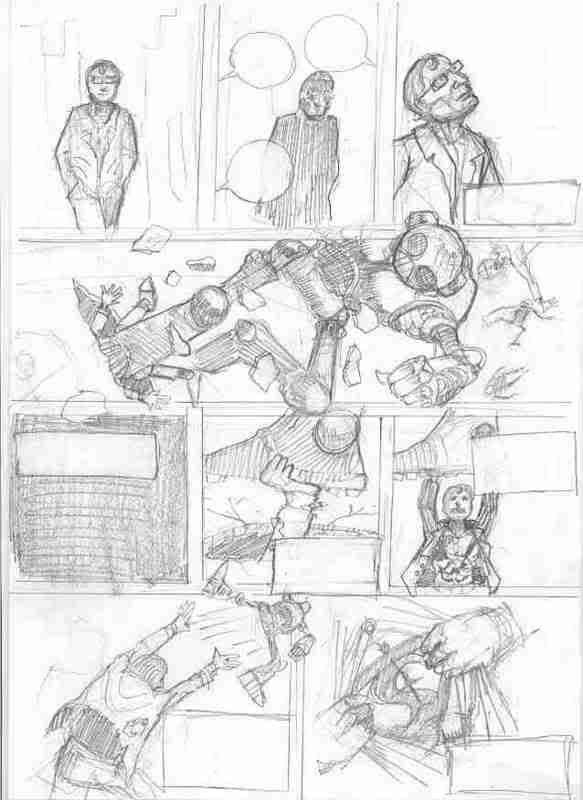

First off, when I read the script, I imagined that the robot had fallen on Clark. So seeing what the artist draws as a very deliberate STOMP is something to consider. the way you write and imagine, might not be what the artist sees and draws and, if you're working on something other than your own project, it might not be how the editor who approves the script before it's passed on to the artist, imagines it.

I also imagined it as the robot accidentally stepping on Clark. The robot is stamping through Metropolis, it crushes a citizen impassively....but that citizen is the last son of Krypton, who throws him away.

BUT, if I got this thumbnail, I would rethink the entire script based around the fact that the robot STOMPED on Clark maliciously. What does this mean? Does the robot know that he's Superman? Moreover, what about the crowds who, panicked or not, did see him pick up and throw a robot? How does this affect things?

AND...if this were real, he would have more than just one page at a time, and I would have told him the story already. So if the robot passively stomped on Clark, he would have understood that from the rest of the script and my storyline synopsis. But as it was, all I gave him was one page of script and nothing else.

Of course, I could have just misread it, but the point is the same. Don't get locked into one ideaof how a page should be.

Second. There could well be someone looking at that artist's version and thinking, "Man that looks rough!"

And it does. If that were all there were to it. But this is a thumbnail. It's a test to see how the page dynamic plays out. This is the test version. Does the script translate to the art? Is there a better way to represent the action? Is there room for all the dialog?

Exactly, and Roughs are vitally important. It tells me if the shot works, or if it botches an emotion. It tells me if what I wrote actually beats out well, or if I've made it too fast, or too slow, or it doesn't flow smoothly from one panel to another.

One thing that Archie comics and Sonic the Hedgehog comics (weird mixture; bear with me) did when I was a kid was, on action pages, they would have arrows going from panel to panel, to make sure you read the right order.

You shouldn't have to do that. You don't have to stick to a set layout, you can have panels moving differently around the page, but the reader should flow between 'em without arrows, you see.

AND it tells me: do I have too much dialogue in a panel? Do I have too many panels without dialogue? Do the panels get the point across?

That first long wide panel is difficult to pull off, because it requires height and the panel doesn't have it, so you need to rotate, but if you rotate too far it's a mess, because unlike a Playdude center-fold, you really DON'T want to have to turn a comicbook 90 degrees to check out a panel. If this didn't work, then we'd need to sit down again and rethink the script. But it's better to discover that NOW than if our artist had simply started doing the really polished version.

This is a fascinating point that I wanted to make too. When I envisioned the panel, I pictured just a level shot of the ground, as if the camera were still looking right-on at Clark, just from lower. We see the foot coming down, and maybe Clark's hand sticking out. That's why I talked about cars flying. Because I was thinking we'd bee able to see straight on down the street.

BUT, he did it differently, (and in his e-mail, he confessed he didn't know what I meant by flying cars, and so he did flying people) and I think he did it better. AND, the fact that he broke out of the panel works extremely well.

But what if it wasn't better? What if it completely blew the point I was trying to make, or ruined the tone I was trying to set? Then this would be where we find out and correct it, when the page consists of some nicely-done scribbly bits and not heavy inking and completed drawings.

(NOTE TO ASPIRING WRITERS - If your artist doesn't do thumbnails, odds are, they are either awesomely talented OR they don't really know what they are doing. You can probably guess which is the more likely of those two scenarios.)

Even if the artist is awesomely talented, even if you're working with Jim Lee (when he's on deadline) or Todd McFarlane (before he was an asshole) then

do your thumbnails. Insist on it. Because it's not only telling you if the ARTIST has a problem, it's telling if YOU have a problem. This is the best, best way to check your script and see how it's flowing. If you have the artistic ability, do them yourself, I guess, but I would rather your artist do them. It helps to build your working relationship, it helps get you on the same visual page if you aren't already, and it means that if things need to be changed, you and the artist can argue about it and change it before too much work has been done. That helps keep tempers cool and egos down.

The artist breaks out of the confines of the panel as well, which adds to the dynamic of that panel. It simply can't contain all the action.

Exactly. And it's something I didn't mention in my script, and the artist did it anyway. If I didn't already know that Chris Saar and I were extremely well-meshed (and I do; visually, we are dead center with each other) this would be the sort of detail that gives it away. This is the sort of important thing to look for.

I didn't tell him to break out of the panel, didn't think of it at all. But after seeing it done, I realize that it's better than what I meant. It serves the comic much better, and I can't imagine NOT having it, now that it exists. That's a good thing. You don't really want an artist who does nothing but copies you, it's good when the artist shows you what you meant, sometimes better than you did. You're a team, after all, not a leader and a follower.

Once this gets the go-ahead, our friendly neighborhood penciler will get out the Bristol Board, maybe the color-safe blue pencil, and start working on the real pages.

And while he's doing that, I'd be off writing more comic script. Which is, in fact, what I'm doing. Chris Saar and I are working on a one-off comic issue. After seeing his superman page come back, I happily went back to work on the one-off issue, though I'd stopped for a couple of days. It reminded me that we work well together, that it's amazing fun, and....er....that I'm over deadline, but nevermind that...

I think this is a really useful thing for this thread (actually, I just think this is a damned useful thread) in that it's important to know how your script translates, what to fight for and what not to fight for.

Plus, there's a thrill of giving the script to someone who gives you back not only what you wrote, but what you

meant that's undiscribeable, and one of the reasons why I keep working on comics, even though I could probably get richer and have less stress if I picked my nose on a streetcorner for money.

This is a good thread, wordmonkey, even if we're the only two reading and replying.....